This spring, Jennifer Crane published her new book ‘Gifted Children’ in Britain and the World: Elitism and Equality since 1945 with Oxford University Press (open access). It expands upon the article “Britain and Europe’s Gifted Children in the Quests for Democracy, Welfare and Productivity, 1970-1990.” Contemporary European History 32, no. 2 (2023): 235-53. For this article, she received an honorable mention for the 2024 Fass-Sandin Article Prize in English by the Society for the History of Childhood and Youth. In this interview, we discuss the twentieth-century concept and legacy of ‘gifted children.’

In your article, you study “gifted children” in 1970s and 1980s Europe, with a focus on Great Britain. For those who may be unfamiliar with this term, what did giftedness mean and what tools were used to assess whether a child was gifted?

Great question! Ultimately the idea of what a ‘gifted child’ was was hugely flexible and ever-changing, over time and space, from the 1940s onwards – and that’s what made the label so appealing and intriguing to many groups . . . for voluntary group the National Association for Gifted Children, a gifted child could walk or talk ‘early’ or even ‘too much’, quickly grasp new ideas, and pay ‘extraordinary attention to detail’. For many psychologists working in the mid-to-late twentieth century, gifted children may be identifiable via ‘intelligence tests’, often scoring 140 or above. These tests were often formed by psychological testing which had sexist and racist outcomes. As a result, of such tests, white, middle-class boys were disproportionately identified as ‘gifted’, while Black children were disproportionately placed in to special needs education. By the 2000s, critique of IQ testing, from campaigners, children themselves, and educational psychologists, meant that such testing was less commonly used to shape educational journeys. Nonetheless, the language and idea of a ‘gifted child’ remained, for example, in the New Labour-funded National Academy for Gifted and Talented Youth – here, gifted children were identified through a broader range of measures, such as via letters from students or marked pieces of work – biases remained, of course, but, for the Academy at least, identifying ‘the gifted’ was intended to form part of a broader social mobility agenda.

As you explain, the concept of the gifted child was not new to the second half of the twentieth century. Why, then, did interest in giftedness surge in Cold War Europe?

Interesting! Yes so the idea of giftedness, like most ideas, has long-standing roots – Sally Shuttleworth has written wonderfully about attitudes to so-called ‘precocious’ children in the nineteenth century. But, at least for the voluntary groups I study in my book, the 1970s and 1980s were a key moment of activism around identifying, helping, and even mobilizing the gifted young. In Britain, the National Association for Gifted Children was particularly active in these decades, because its parent-members were keenly feeling a sense that provisions in the welfare state and education were declining – in place of this, they worked collectively, looking to provide summer and weekend clubs to stretch, challenge, and entertain their children. In the final chapter of my book, I look also at two transnational organisations, again especially active in these years, the European Council for High Ability, founded in 1988, and the World Council for Gifted and Talented Children, founded in 1975. Acting within a broader context of thinking globally about human rights in these decades, both organisations hoped that identifying the gifted young, across national borders, could be valuable – potentially even playing a part in easing humanitarian crises, global disputes, and economic decline.

You note that certain types of parents tended to be most actively invested in giftedness. Can you tell us more about this group: Who were they, why did they care about this designation, and what does their activism tell us about ideals of parenting, education, and child welfare in Margaret Thatcher’s Britain?

As mentioned, the majority of parents who joined the National Association for Gifted Children in Britain, from the late 1960s until the 1980s, emphasized that they felt failed by the welfare state, which did not provide adequately for gifted young people in this period. This was, they often emphasised, in tension with stated post-war ideals of state education as catering for all abilities. Another reason often given by parents, for joining such voluntary groups, was that they felt lonely, isolated, and sad, as parents of the gifted young. In 1969, the BBC programme Horizon aired a documentary about giftedness where, on these lines, a mother emphasised how isolated and even socially stigmatised she felt, due to how unusual her child was. Other newspaper accounts, in subsequent decades, reported that marriages had ended over the strains of raising gifted children, and that parents felt ‘embarassed’ and ‘bewildered’. The fact that these accounts were shared and disseminated speaks to a broader context in this period, where media, policy, and campaign groups asserted that experience and emotion mattered and that ‘family issues’ previously seen as ‘private’ should be aired, shared, and learnt from. This was a period in which campaign groups also became savvy users of an interested media.

I loved that your piece included sources from gifted children themselves. Based on what you read, how did gifted children feel about their status? Were they excited to be “gifted” or did they chafe against this label?

Reading sources from children themselves labelled as gifted was my favourite part of this research project. There are rich archives available of children’s writings in the mid-to-late twentieth century, as writing was increasingly seen as a key part of children’s educational development. Gifted children, especially, were often asked to record their views, notably through the newsletters and magazines of giftedness groups, precisely because these young people were often identified as ‘elites of the future’. As you can imagine, children identified as gifted had a range of views about this label. For some, it was a gateway to enjoy exciting new leisure pursuits and activities, and to make friends who shared their interests and passions. Children reported feeling shy or timid, bored or restless, before this label enabled them to access new extracurricular spaces, for example. Other children though, saw the label as arbitrary, questioned the psychological and educational systems underpinning it, and complained about the pressure and expectations entwined with ‘gifted life’. Some children, radically, asked why we should promote children’s ‘giftedness’ or intelligence, rather than look to maximise their happiness or wellbeing.

I was also fascinated by the way that commercial entities leveraged the concept of gifted children to sell products––it reminded me a bit of Amy Ogata’s research into “creativity” and design in the midcentury US. What was the funniest product you found that promised to draw out a child’s inner gifts?

Haha! Well something I’ve always found fascinating is the idea of playing a CD over a pregnant stomach, particularly a CD of classical music, hoping to aid a child’s brain development – the ideas of body as porous surface, womb as space of future potential, classical music as particularly powerful, all fascinate me and I want to follow this interest up. But the first advert I remember seeing about giftedness, which really interested me, was one from the early 1950s promoting Horlicks in The Times. I just found it fascinating that the advert framed consumption of this whole product around giftedness – stating that gifted children were ‘the most highly strung’ and that a malted drink could give them stamina and nourishment. I had to follow up and know more about what gifted children were expected to be like, this perception of their distinct energies and movements, and how various groups hoped that such children could be mobilised.

You just published your monograph ‘Gifted Children’ in Britain and the World: Elitism and Equality since 1945—congratulations! How does this book continue the theme of your article?

Thank you so much! So my article looked at the 1970s and 1980s in particular, and at how concerns about the gifted young shaped ideas of a ‘united Europe’ – it also started to look at how families and children themselves felt about being conceptualized as key actors in this configuration. The book takes this further. Central across the book are the testimonies of children themselves – how they saw ideas of measurement; the critiques they made of sexism and racism; how this label shaped their interactions with teachers, parents, and peers, all examined via poetry, letters, and articles. The book also looks at a much broader time span than the article – it starts in the 1940s, and shows that, of course, people cared about ideas of intelligence and stupidity, in everyday life, in this decade. Nonetheless, it also argues that distinct and significant new cultural and lived interests in ‘gifted’ children – who were hyper-intelligent – emerged from the sustained work of some remarkable, charismatic campaigners in the 1960s. The book ends in the 2000s and thinks about how ideas of ‘giftedness’ were somewhat challenged or obscured by those of ‘aspiration’ by this period. For example, this is visible in the production and keeping of bulky, eagerly catalogued National Records of Achievement. The book argues that longstanding and longshifting debates about giftedness, overall, showed constant tensions between diffuse and ill-defined ideas of ‘equality’ and ‘elitism’ in modern Britain – frequently, gifted children were presented as potential ‘elites of the future’ and yet campaigners stated that not identifying them was an issue of social justice and also that identifying them could actively solve broader social inequalities, for example. Within and across such debates, I argue that the gifted young themselves exercised ‘agency’ – they saw these multiple conceptions at work and sought to use them to access new leisure spaces, critique adult-led policies, and remake their daily lives.

Are there broader misconceptions or harmful narrative about ‘gifted children’ that you are hoping to reframe with your book?

I think that a valuable reminder, from the child-written sources, is that these were ultimately children. If we read policy debates or those of transnational organisations, the hopes placed on gifted children were sky high – international exchange schemes, training, discussions. There were hopes that the gifted young could solve a host of current or future problems. But reading children’s own poetry or letters and comparing them to those of general cohorts of school children in this period, we’re just reminded of the interests of their daily lives – animals, circuses, space, buildings, bullying, friendships, playgrounds – these things, and more, deeply occupied many children’s attention, regardless of whether they were labelled ‘gifted’ or not.

It would be great to know more about the process behind your research: How did you arrive at studying giftedness and what were the first steps you took for grounding this intellectual and cultural concept in a set of concrete historical sources?

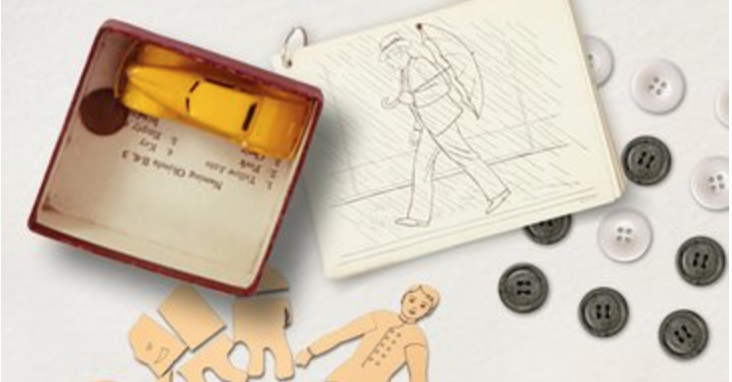

As mentioned above, I was really drawn to this 1950s advert and initially just fascinated by the idea that people who were hyperintelligent may have some specific kind of nervous energy. I developed this project following broader interests in experiential expertise, the power of labelling, in spaces conceptualized as distinct to children’s voluntary and extracurricular lives, and in welfare state ‘failure’ or gaps. I also became very interested in transnational networks and activism, and in penpal networks and international exchanges. I was lucky enough to be awarded a 3-year Wellcome Research Fellowship to pursue this research (back in 2018), which was a huge privilege and came from a lot of luck. This enabled me to follow these interests broadly and experimentally, looking through maybe 20 or so physical and online archives and tracing how this key word, ‘gifted’ (and associated words, ‘intelligent’), travelled, and the affective pulls and potentials of ‘giftedness’ for different groups. I was able to look at the material cultures of historic IQ tests (as featured on the book cover), passionate debates at educational conferences, child-produced magazines, full of drawings and poetry, and the newsletters of globally-oriented voluntary organizations. I was hugely influenced in then thinking more conceptually about this material by a reading group organized by Dr Sian Pooley, called the ‘monkey minds’ due to some pandemic-related group hysteria – Sian is an incredible scholar of childhood and encouraged us all to think very critically about concepts such as ‘agency’ and ‘experience’, as well as to value and unpick the distinctiveness of child-produced sources, across times and spaces.

To end on a personal note, we’d like to ask you about a few of your favorite things…

a. Favorite way of managing notes and/or citations?

It’s not good . . . I just do them by hand, manually – I’m sure that I should get a software management system but am hiding behind the excuse that it would not catalogue my archive materials accurately.

b. Best book in the history of childhood and youth you’ve read in the past year (does not have to be something that was also published in the last year)?

It’s from 2021 but I thought that Emily Baughan’s Saving the Children: Humanitarianism, Internationalism, and Empire was fascinating and such a careful, critical account of the symbolism of children in humanitarian action. Caitriona Beaumont, Eve Colpus, and Ruth Davidson’s new book, on Everyday Welfare in Modern British History, has lots about children and families, and I particularly loved Eve Colpus’s chapter on experiential expertise in ChildLine, and children’s ‘subversive acts’. Looking to the future, I’m looking forward to reading Hannah Elizabeth’s forthcoming book about reinventing childhood in the age of AIDs – I know from their presentations and recent work that this will provide radical, critical, and child-centric new perspectives on childhood, medicine, and discrimination in this period. I’m also looking forward to the upcoming collection on Nordic Neoliberalisms edited by Jenny Andersson and Chris Howell, which has chapters on welfare states and also on family-state relations in ‘neoliberal times’ (the latter by Cecilie Bjerre and Klaus Petersen). Finally, this year I’ve been really interested by a growing body of work around children and climate change – in particular I loved this piece on ‘our children’ as a trope in climate change discussions, and this (related) one on the ‘Anthropocene child’, ‘called to act as the earth’s and humanity’s protector’.

c. Favorite childhood game or toy?

Immediate things that come to mind are the desperate (unlived) dream to own a Furby, the joyful manic care provided to a Tamagotchi, the frustration, rage, perhaps full-on tantrum when trying out a magic set gifted one Christmas, and unable to do the tricks. This was all last year, of course.

d. Best piece of advice you got as a child?

That’s really interesting and you know I really really can’t remember . . . I’m sorry!

e. And in keeping with the theme of the piece, did you ever have to go through standardized testing in school? If so, what was your favorite or least favorite test experience?

I remember some kind of test that everyone in my primary school was doing, very young, and that we all got a biscuit after doing it, so I felt relatively relaxed and excited. I then vividly remember the stress ramping up in subsequent years, and certainly felt that GCSEs, A Levels were very intense, with a lot to remember, and acute awareness of being compared, measured, ranked, with distinct potential ‘futures’ at stake. I also found sports days a test – and actually, reading the wonderful Opie archives and looking at the 1950s, remembered a lot of childhood chants and games had persisted in to my 1990s childhood too.

Jennifer Crane is a senior lecturer in health geographies at the School of Geographical Sciences, University of Bristol, working at the intersection of history, geography, and sociologies of health. She has published popular and scholarly works exploring how diverse publics access state welfare, analysing diverse case studies of child welfare, the NHS, and gifted children. Much of her work has employed and driven new analysis of ‘experiential expertise’.

Parts of this interview are adapted from Jennifer Crane, ‘Gifted Children’ in Britain and the World: Elitism and Equality since 1945 (Oxford: OUP, 2025). This is an open access publication, available online and distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. With thanks to Wellcome grant ‘Constructing the “Gifted Child”: Psychology, Family, and Identity in Britain since 1945’ (212449/Z/18/Z) for funding this research.