Follow along to read the entire comic strip by Bevs Boredom Comics!

Growing up the in the 1990s and 2000s, the first game that I played and completed with my sister by my side was The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time.1 One of my most cherished memories is my overwhelming excitement that the digital in-game horse, Epona, liked the playable character I was using, Link. This meant that later in the game, I could ride Epona and reach different areas in the game world. In that moment, I imagined Link to be happy and expressed that happiness on screen by making Link do backflips to share the excitement with my sister. This combination of player imagination and designed interaction between the gameplay and story is an example of care play.

Care play is a concept I developed during my dissertation exploration of videogames, girlhood experiences, and select games from The Legend of Zelda series.2 Care play are actions or thoughts by videogame players towards a videogame character that resemble care work. This helpful, kind behavior can be performed towards designed avatars, playable characters, or non-player characters (NPCs). This connection exists in a spectrum from totally designed, imagined, or somewhere in between, and can be done explicitly or subtly by the player towards the videogame character. Looking at the relationship between videogames, related visual and material culture, and ethnographic interviews to better understand girls’ experiences gaming in the 1990s during my dissertation led me to think about the many ways young people play and are invited to play. The women and nonbinary participants I interviewed shared similar tales of caring for Epona and helping the titular Princess Zelda. I found time and time again that a player’s desire to be kind eclipsed their perception of what had appeared on screen. While the mainstream narrative continues to be that videogames predominantly involve violent play and are masculine-coded, care play provides a way to think about more kinds of videogame play.3 In this article, I will share some of care play’s possibilities using case studies involving narrative and material culture’s impacts on historical interactive play marketed towards younger players.

Tracing trends back to Victorian to mid-century American records, Shira Chess explains that boys’ play has been linked to new and developing technologies and has now become synonymous with videogames, while girls’ play remains rooted in traditional, nurturing play in preparation for future, expected roles as mothers and caretakers.4 Sara Grimes reinforces this with her findings evidencing that girls are more likely to be assigned chores, even up into the mid-2010s.5 This established link between traditional gender roles, which requires girls and then women to perform care work, gave me pause when pursuing care play as a method of examining the less explored aspects of gaming. It is my intention to add to the tools for examining historical gaming created for and utilized by young people, especially marginalized groups based on gender, race, ability, and other identity factors. I will show how care play illustrates the affordances of videogames for young people rather than reinforcing assumptions about their videogame play.

Many younger people growing up in the 1990s had the opportunity to play with videogames through consoles, computers, and bespoke products. One of the most popular was the Tamagotchi (and, if you are reading this, you may have been one such kid!). Tamagotchi are digital pets that players must care for throughout the day, requiring lining up the device with the player’s time zone and then feeding the Tamagotchi, cleaning up their excrement, giving them gifts, and playing minigames with them. A Tamagotchi lends itself to a material culture review of care play. Borrowing Robin Bernstein’s insightful terms, a Tamagotchi is a “scriptive thing”, “hailing” the player to engage with it by way of a convenient console and a cute, fictional creature.6 In other words, the physical design of the Tamagotchi and the charming cartoon creature encouraged young people to take it with them and care for it. Because the Tamagotchi creature aligns with player time zones, the existence of the digital creature can become part of a player routine. Unlike computer games or videogames requiring consoles, Tamagotchi exist in their own small, keychain devices designed for players’ convenience. It was, and still is, easy to attach Tamagotchi to backpacks, purses, belt loops, etc.7 This designed play, akin to what Adrienne Shaw refers to as “dominant” or “hegemonic” use “encoded” into the object, is one element of care play in videogames.8

Where Tamagotchi represent a direct example of care play, the Pokémon games instead encourage a combination of gameplay influences from the developer and player, like the “negotiated” play Shaw observes.9 While Pokémon are also cute, fictional creatures and do occasionally need to be fed like Tamagotchi, caring for Pokémon is only a part of the larger goal of winning battles.10 Feeding Pokémon berries and healing potions increases their health points and allows them to continue fighting. Once the Pokémon run out of health points, they are defeated, and the player therefore loses the battle. However, players can give Pokémon healing items when they have full health. For instance, perhaps a player wants to give a berry as a treat to their favorite Pokémon not being used for battle because it is cute or they imagine it feels left out. This scenario is like a pet-owner relationship between the player and the digital creature, exists in opposition to the main goal, battle strategy, and is what Stephanie Boluk and Patrick LeMieux refer to as the “standard metagame.”11

The standard metagame includes the videogame goals and designed pathways that are the intended way to play, or what Shaw refers to as “encoding”.12 Unlike care play, the more mainstream videogame goals are frequently based around destroying progressively more challenging enemy characters culminating in boss fights with antagonist characters. This core gameplay, story, and related goals are described as the standard metagame. More video and computer games use violent challenges as the main hurdles to progress than non-violent challenges like puzzles.13 This is, and has been, apparent for decades in the depiction of, often male, protagonists wielding weapons, and continues today in game trailers advertising avatars wielding different weapons and moves.14 Yet as Shaw notes, “[designs] and environments like media representations do not tell us what to think or do, but they do shape what we think with”.15 Healing items are intended for and useful as support for the turn-based combat system, which involves one or more videogame characters sequentially attacking the enemy and healing themselves or their team. However, players can ultimately use healing items to care for Pokémon how they see fit.

The Pokémon series are not the only games that focus on defeating enemies while also making space for care play. Despite its ESRB (Entertainment Software Rating Board) rating M for Mature for exclusively adult audiences, Ghost of Tsushima includes care play gameplay.16 In Ghost of Tsushima, players have the option to pet a series of animals guarding shrines as the stoic, wandering ronin. These games supersede a gendered segregation of care play for girls and videogames for boys by featuring care play in big releases often referred to as triple-A (written as AAA) or hardcore games.17 Game development has progressed such that longer storylines, more goals, and a greater number of player options are possible. Thanks to advances in memory storage, internet connectivity in videogames, and the prevalence of additional DLC (downloadable content), it is now easier than ever to incorporate care play in even the most violent games.

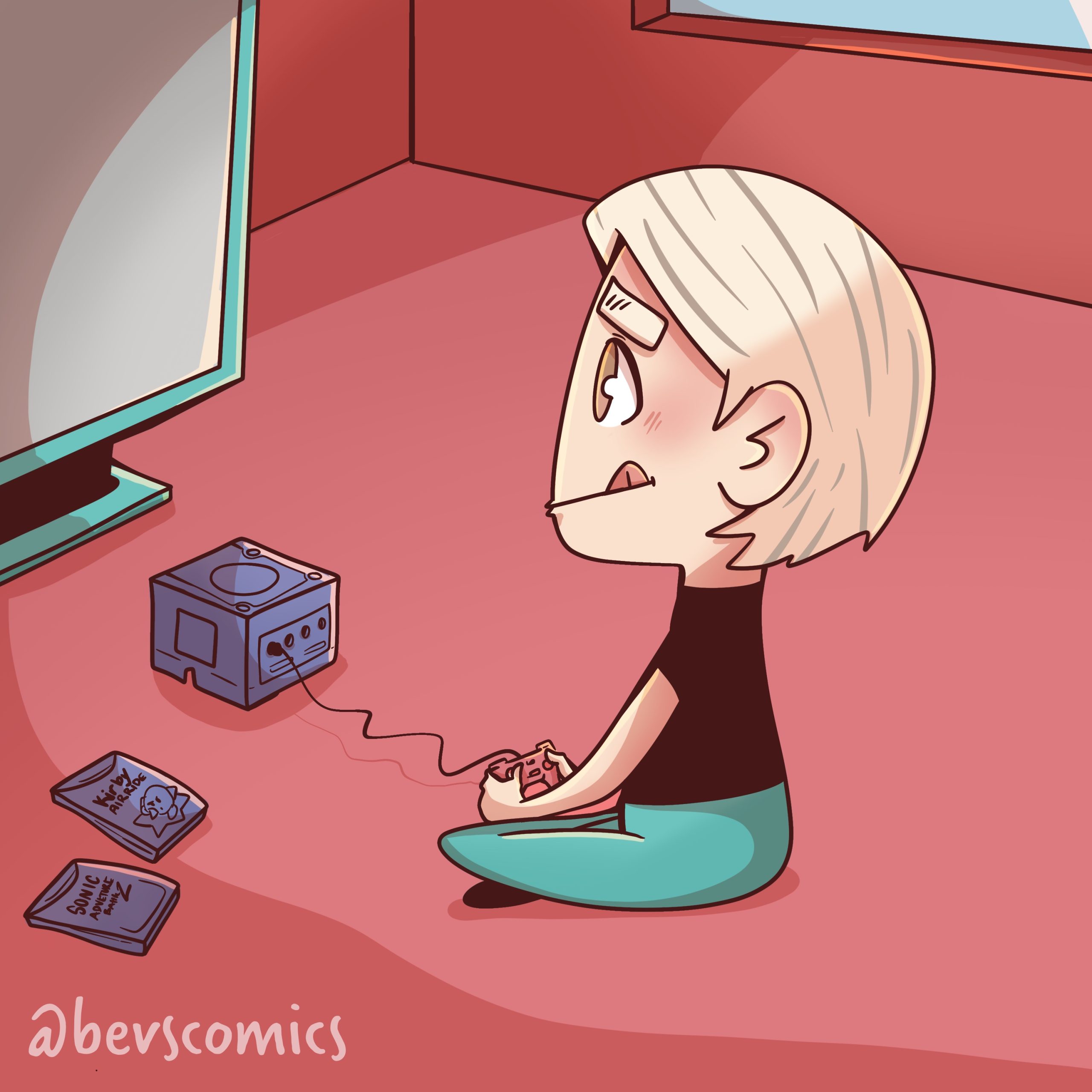

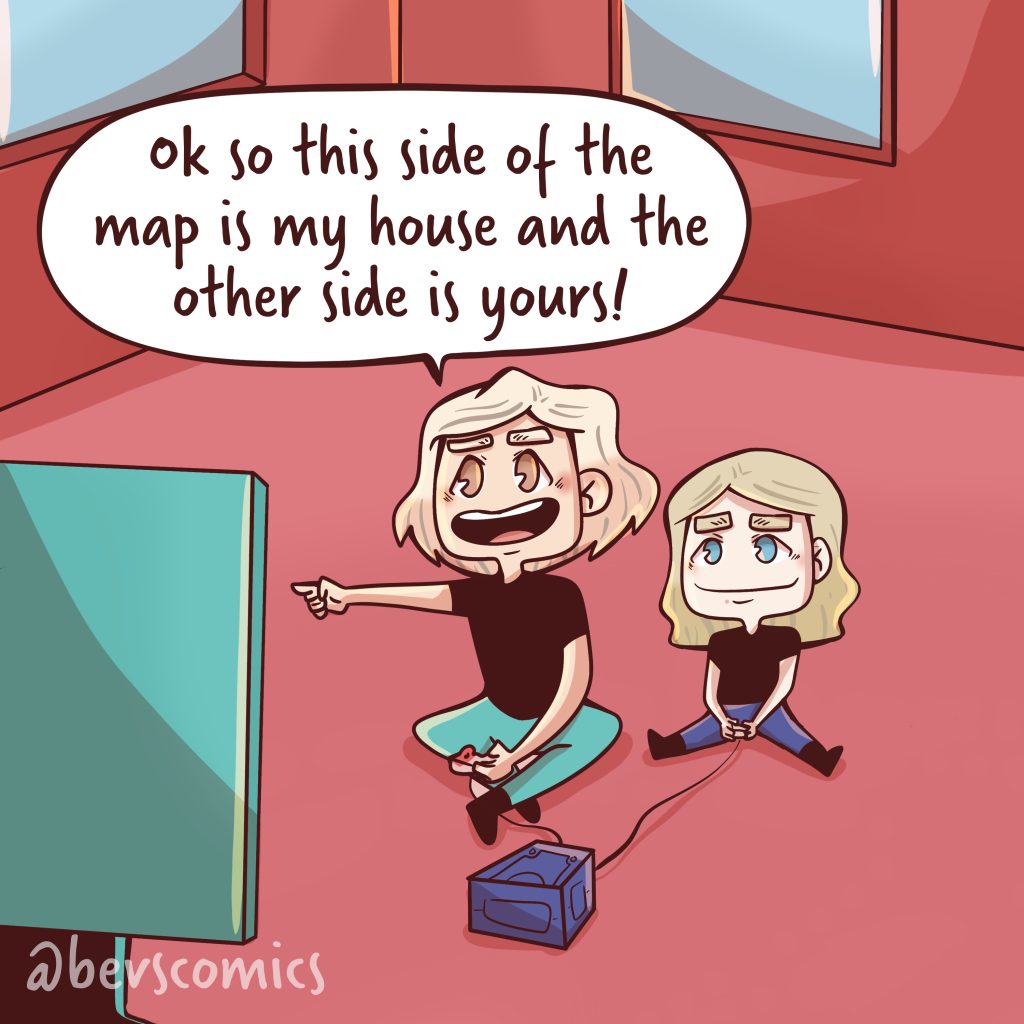

Finally, when young players have the freedom to move characters around, this creates the potential for them to build off the story created by the game designers or use the assets to create their own unique stories, particularly in interactions between characters. With the ubiquity of consumable media, children often interact with established characters in franchises. As Kathryn Hemmann explains in her work about female fans, they “view media properties not as passively consumable content but rather templates from which more personalized and individually meaningful stories can be created”.18 For example, Bev Comics creator, Krysten Bevilaqua, tells a story through her Instagram cartoon about playing house with her sister using the Super Smash Bros.19 The Super Smash Bros. franchise is a series of fighting games, pitting Nintendo characters from different games against each other and later incorporating characters from other publishers and consoles. Not only were Bev and her sister resisting the standard metagame by not fighting against each other per the main goal of every match of the game, they also further made the established characters their own by changing the context of their interactions. Bev and her sister took up Shaw’s “oppositional” use of the game and created imagined domestic relationships between the characters they selected.20

From an interactive story perspective, performing kind actions towards characters through care play, whether designed or imagined, fleshes out the videogame world the young player inhabits. Rather than just a grand, epic adventure, this encompasses more relatable everyday struggles and accomplishments. Author Ursula K. le Guin posits a “Carrier Theory of Fiction” asserting that novels are shaped more like containers of mundane but meaningful and practical objects rather than the elevation of a masculine heroic figure.21 Since the introduction of open worlds in console games in the 1980s, game worlds offer many smaller, personal, and caring moments for young players to discover, create, and negotiate.22 Players can interact with multiple NPCs throughout game worlds, providing narrative opportunities for helpful, designed gameplay or readings of the dialogue as caring between the characters.

Both the carrier theory and care play actions, more relatable than mainstream videogame violence, create a link between gaming and life discussed by Laine Nooney. Nooney explains that gaming should fit into life, not the other way around.23 Because care play is less likely to be part of the larger, more challenging, main game goals, care play tends to be less involved and time-consuming, allowing it to fit into more varied schedules, such as before school and between chores. Relatedly, the way that Tamagotchi offer mobility and sync up with players’ schedules provide short care play breaks directly and physically aligning with Nooney’s suggestion. Play that fits into young people’s schedules connects directly to historical girls’ play and how household chores continue to be gender segregated.

Despite these connections, care play does not need to perpetuate traditional gender roles. Moreover, the more common violent standard metagame does not need to be the only way to complete all or part of videogames. In the most recent addition to The Legend of Zelda franchise, The Legend of Zelda: Echoes of Wisdom, the titular Princess Zelda is the protagonist, and her main goal is healing her Kingdom of Hyrule.24 Young players, as is implied by the E for Everyone rating, are actively invited to accomplish the main goal of healing care play through a variety of methods, often creating “echoes” of previous enemies to defeat new ones through Princess Zelda’s magic. For limited periods of time, players can fight with a sword and shield like in previous Zelda games, and later the player-as-Princess-Zelda coordinates defeating enemies and completing puzzles with the original protagonist, the male hero Link. Though Princess Zelda’s name is part of the title, the main playable character is usually Link. The game even references his established role during the closing cutscene when the townspeople NPCs congratulate Link on his heroic rescue of Hyrule. As a silent protagonist, players are invited to infer what Link is saying through his gestures. Is he making jokes or is he giving a classically sincere heroic speech? Regardless of how the young player chooses to interpret it, they see Link indicate through gestures that it was instead Princess Zelda who saved the day.

Elevating care play to a starring role in the gameplay and story in The Legend of Zelda: Echoes of Wisdom helps legitimize this less traditional form of videogame play and draws attention to its role in gaming history. Centering care play exposes young players to a greater range of gameplay options. Requiring Zelda and Link’s distinct skill sets puts them on equal footing, at least for this game, and can serve as a reminder that players-as-Link have used care play to complete past challenges in the Zelda franchise. For instance, Link used a song called “Song of Healing” in The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask to help numerous NPCs.25 Both games introduce young plays to a highly valued form of care play and indicate that it is okay and fun to accomplish things in more ways than one, and to sometimes let someone else be the hero.

With this article, I present care play as a theory that helps videogame researchers, especially those who study young people, have a more comprehensive view of a game’s nuances and impact. It is the combination of accomplishments inside the game, interpretations by players, and the relationships to characters that teach us more about real-world interactions. Yes, games can, and often are, big and bombastic. But sometimes, heroic actions are small. Defeating enemies may often be part of the quest, but so is saving, healing, and even just listening to others. Is that not what you do when you care about someone? After so much time playing with them, you come to care about videogame characters. At least, I know I do.

Kacey Doran (she/her/hers) received her doctorate in Childhood Studies from Rutgers-Camden and is the Esports Academic Coordinator at Rowan University. She has an M.A. in Children’s Literature from Hollins University and a B.A. in Women’s and Gender Studies from West Chester University of Pennsylvania. Her dissertation focused on alternative perspectives of The Legend of Zelda franchise through feminist humanist and qualitative research methods analysing videogames, visual and material culture. Contact her at dorank@rowan.edu.

- The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, Nintendo, 1998. ↩︎

- Kacey Doran, My Link to the past: expanding conceptions of girlhood play with the Zelda franchise (Rutgers University Libraries, 2022) 1-222. [https://rucore.libraries.rutgers.edu/rutgers-lib/67543/] ↩︎

- For context to how privileged, white boys and men became the “default gamer[s]”, see work by scholars such as Mia Consolvo, Kishonna L. Gray, Lisa Nakamura, and Adrienne Shaw.

Mia Consolvo, “Crunched by Passion: Women Game Developers and Workplace Challenges,” Beyond Barbie and Mortal Kombat: New Perspectives on Gender and Gaming, eds. Yasmin B. Kafai, Carrie Heeter, Jill Denner, and Jennifer Y. Sun (Cambridge, London: MIT Press, 2008), 177-192; Kishonna L. Gray, “Deviant Bodies, Stigmatized Identities, and Racist Acts: Examining the Experiences of African-American Gamers in Xbox Live,” New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia 18, no. 4 (2012): 261-276; Lisa Nakamura, “Queer Female of Color: The Highest Difficulty Setting There Is? Gaming Rhetoric as Gender Capital,” Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology 1, no. 1 (2012): [http://adanewmedia.org/2012/11/issue1-nakamura/];

and Adrienne Shaw, “Do You Identify as a Gamer? Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Gamer Identity,” New Media & Society 14, no. 1 (2012): 28-44. ↩︎ - Shira Chess, Ready Player Two: Women Gamers and Designed Identity (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2017), 2-3. ↩︎

- Sara Grimes, Digital Playgrounds: The Hidden Politics of Children’s Online Play Spaces, Virtual Worlds, and Connected Games (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2021), 50-51. ↩︎

- Robin Bernstein, “Dances with Things: Material Culture and the Performance of Race,” Social Text, 27, no. 4 (2009): 67-94. ↩︎

- Tamagotchi have recently returned to the market. I was able to model the above figure off an anniversary Tamagotchi I bought several months before writing this article. ↩︎

- Adrienne Shaw, “Encoding and decoding affordances: Stuart Hall and interactive media technologies,” Media, Culture & Society 39, no. 4 (2017): 592-602. ↩︎

- Shaw, “Encoding and decoding affordances,” 598. ↩︎

- Pokémon, Game Freak, Nintendo, 1996. ↩︎

- Stephanie Boluk and Patrick LeMieux, Metagaming: Playing, Competing, Spectating, Cheating, Trading, Making, and Breaking Video Games (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017). ↩︎

- Shaw, “Encoding and decoding affordances,” 593. ↩︎

- Chess, Ready Player Two, 4. ↩︎

- For context on how violent, masculine-coded gameplay became the standard metagame for videogames, see work by scholars such as Carly A. Kocurek, Robert Mejia and Barabara LeSavoy, and Adrienne Shaw.

Carly A. Kocurek, Coin-operated Americans: Rebooting Boyhood at the Video Game Arcade, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015); Robert Mejia and Barbara LeSavoy, “The Sexual Politics of Video Game Graphics,” Feminism in Play, eds. by Kishonna L. Gray, Gerald Voorhees, and Emma Vossen (New York: Palgrave, 2018), 83-101; Adrienne Shaw, Gaming at the Edge: Sexuality and Gender at the Margins of Gamer Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015). ↩︎ - Shaw, “Encoding and decoding affordances,” 596. ↩︎

- Ghost of Tsushima, Sucker Punch Studios 2020. ↩︎

- AAA or hardcore games are more expensive, longer, and feature more challenging gameplay than casual games. Shira Chess and Christopher A. Paul, “The End of Casual: Long Live Casual,” Games and Culture 14, no. 2 (2019): 107-118. ↩︎

- Kathryn Hemmann, “The Legends of Zelda: Fan Challenges to Dominant Videogame Narratives,” Woke Gaming: Digital Challenges to Oppression and Social Justice, eds. Kishonna L. Gray and David J. Leonard (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2018), 213-228. ↩︎

- Super Smash Bros. Nintendo, 1999. ↩︎

- Adrienne Shaw, “Encoding and decoding affordances,” 598. ↩︎

- Ursula K le Guin, “The Carrier Theory of Fiction,” (1986) 165-70. ↩︎

- Good examples of these are the game worlds of Super Mario Bros. and The Legend of Zelda. Players were able to find secrets and characters to interact with throughout the maps. Super Mario Bros., Nintendo, 1985; The Legend of Zelda, Nintendo, 1986. ↩︎

- Laine Nooney, “A Pedestal, A Table, A Love Letter: Archaeologies of Gender in Videogame History,” Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research 13, no. 2 (December 2013): [http://gamestudies.org/1302/articles/nooney] ↩︎

- The Legend of Zelda: Echoes of Wisdom, Nintendo, 2024. ↩︎

- The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask, Nintendo, 2000. ↩︎