For the year of 2025, the Society for the History of Children and Youth (SHCY) has awarded the Grace Abbott Prize to Divya Kannan’s Contested Childhoods: Caste and Education in Colonial Kerala published by Cambridge University Press. The prize honors the best 2024 English-language book in the history of childhood and youth. Thank you to Divya Kannan for sharing some glimpses into this impressive project that sheds new light on the history of education in colonial Kerala.

Congratulations on this well-deserved prize, Divya! What excites you the most about the main argument of your book?

Thank you! What excites me most is how the book rethinks Kerala’s celebrated educational history by centering the “poor child.” Contested Childhoods shows that colonial schooling was never simply a story of progress or benevolence. Instead, it was deeply entangled with caste hierarchies, missionary agendas, and the political uses of childhood. By tracing how Protestant missionaries, princely states, and poor families negotiated the meaning of education, I show that Kerala’s modernity was shaped as much by exclusion as by reform. The argument that schooling for poor, low-caste children helped the colonial and princely states defer their welfare responsibilities continues to feel strikingly relevant today.

For those who do not study mission history, can you explain why Protestant missionaries were so keen on educating children?

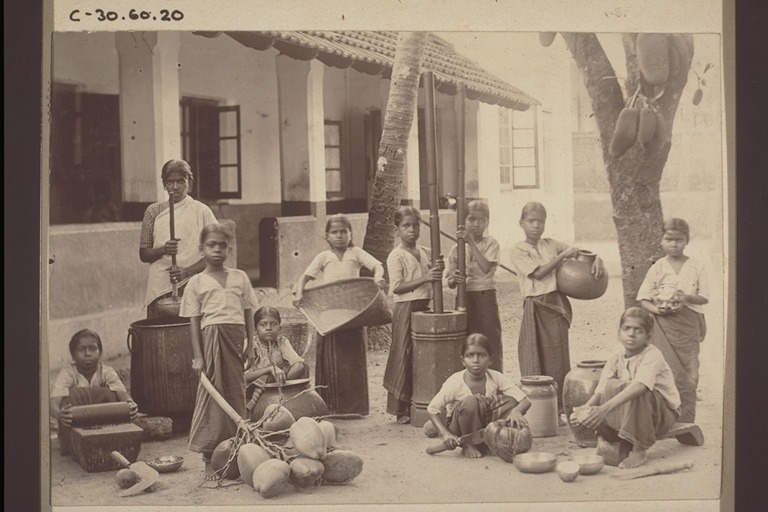

The European Protestant missionaries accumulated a massive archive that is helpful for those working on theology, religion, and secular topics. Their key motives behind educating children in the colonies were to proselytise and discipline them according to their Christian tenets. For missionaries, education was inseparable from evangelism. They saw schooling as praeparatio evangelica—a preparation for receiving Christianity and European civilization. In Kerala, where caste hierarchies restricted who could learn to read or write, the school became a strategic site for transforming both belief and behaviour. Teaching literacy was a way to instil new habits of discipline, timekeeping, and morality. While they initially hoped to convert upper-caste elites, missionaries soon focused on Dalit and poor children, who were viewed as more open to Christian influence. Yet this education also had unintended effects—it allowed marginalised groups to claim dignity and rights in new ways.

What does the “poor child” as opposed to the innocent, wealthier child teach us about the history of missionary education in Kerala?

The category of the “poor child” refers to those belonging to historically oppressed and marginalised castes in my region of study. It refers to their socio-economic status as “poor” beings. At the same time, missionaries also perceived them as suffering from a moral and spiritual lack. The “poor child” reveals a parallel story of colonial childhoods that rarely fits the sentimental image of innocence. Poor and untouchable children were portrayed as “degraded” or “animal-like,” and schooling was meant to civilise and discipline them into productive labourers and obedient subjects. Yet their schooling also became a means of aspiration. These children and their families saw education as a path to self-respect and mobility. The contrast between the pitiable poor child and the cherished elite child shows how ideas of moral worth and social hierarchy shaped the very category of childhood.

How can historians avoid reading children in mission schools as “tabula rasas,” as objects to be inscribed by missionaries?

I think historians must avoid reading any individual or social group as tabula rasas, regardless of the sub-field. It’s important to see children not as blank slates but as historical actors with what Arunima Datta calls “fleeting agencies.” Even within tightly controlled missionary spaces, children resisted, negotiated, and reinterpreted adult expectations—by refusing tasks, running away, or subtly subverting authority. Historians can trace these acts by reading archives “against the grain,” paying attention to silences, contradictions, and emotional undercurrents in missionary reports. Agency need not be heroic to be meaningful; it often resides in the smallest gestures of everyday life. In the case of studies on education and Christian missions, we must be cognisant that individuals had a sense of identity and history before their encounters with “outsiders.”

What kind of sources do you use to trace the compliant, resistant, agentic “subaltern” child in mission schools? How do these sources limit your work?

It is always difficult to discern the “voice” of the subaltern, let alone the child, in archival records. I tried to read the existing sources against the grain but also trained myself to ask different questions. Instead of reading missionary sources, for instance, at face value, I began to ask why and how. If I came across a report by a missionary or a native teacher on the “misbehaviour” of a child, I asked if the writing was more about the former’s perception and feelings than the actual events on the ground. I also used the periodicals written for European children to understand this further. If references were made about colonial children, I differentiated the representation of the “ideal” child and the “actual, real” child the writer was dealing with. There are, of course, limitations to finding sources relating to children in the colonies. They rarely left any records of their own and even in the 20th century, with the spread of children’s magazines, the middle-class, literate child was overwhelmingly represented. It limits my work if I am just hell-bent on finding “children’s voices.” Instead, I try to understand the phenomenon of childhood formation and childhoods that allows me to bring in a variety of social actors and institutions and expand the ambit of investigation better.

What differences did you observe between British and German missionaries’ ideas of colonial childhoods?

British missionaries of the London Missionary Society (LMS) and the Church Missionary Society (CMS) often stressed moral uplift and self-improvement, linking literacy with civic virtue. German missionaries of the Basel Mission, shaped by Pietism, emphasised discipline and spiritual rebirth, sometimes through severe corporal punishment intended to “break the will” of the child. Despite these differences, both shared a racialised belief that colonised children required correction and training. Yet they also depended on these same children’s labour and emotional performances to sustain their missions—an irony that speaks volumes about the contradictions of evangelical child-saving. The German-speaking missionaries of the Basel Mission belonged to agricultural, artisanal families in Wurttermberg. They placed a great emphasis on corporal punishment in their interactions with colonised children. The Basel missionaries were also keen to promote the use of the vernacular language and insisted on their pupils, especially boys, taking up apprenticeships and working in close-knit communities. The British missionaries tended to be a bit more flexible in such matters. Given their proximity with the British colonial administration in India, they also geared their pedagogical training to suit official requirements. Finally, they accommodated caste hierarchies in their churches and schools unlike the Germans who largely resisted it.

What does nineteenth-century colonial education in Kerala teach us about the intersections of caste and childhood? How did caste complicate ideas of childhood?

Caste fundamentally determined who could be seen as a “child.” Upper-caste children were idealised as innocent and educable, while Dalit and labouring children were cast as impure and undeserving of protection. Missionary and princely schools reinforced these hierarchies even as they claimed to offer “education for all.” Separate schools for untouchable children, often underfunded and short-lived, reproduced exclusion under the guise of reform. Caste thus denied the universality of childhood, tethering education to moral worth and social rank.

A continuous thread running your book is the issue of labor. How do you as a historian position colonial childhoods within the history of economics?

Labour was central to missionary and colonial visions of childhood. Poor children’s schooling often aimed to produce disciplined, semi-skilled workers for mission industries or colonial economies. The Basel Mission’s workshops and printing presses exemplify this. Education and labour were not opposites—they were intertwined moral economies. I position colonial childhoods as sites where economic productivity and moral reform converged, anticipating modern debates about child labour, schooling, and social mobility. One of my chapters looks closely at primary school textbooks and the teaching of political economy to pupils. Influenced by Irish and British schoolbooks in previous decades, these books attempted to promote ideas of labour, wages, capitalism to working-class children.

What unexamined themes or ideas do you envision the next researcher building on your book will explore?

Future scholars might explore children’s emotions and sensory worlds more deeply—how fear, desire, or play shaped their experiences of schooling. Another direction is comparative: connecting Kerala’s “missionary schools” with similar institutions in Africa or the Pacific to understand the global circuits of “missionary modernity.” I also hope researchers will examine postcolonial continuities—how today’s educational ideals in Kerala still echo nineteenth-century moral and class hierarchies around the “good” and “poor” child. I also hope there will be further research on colonial textbooks and print cultures and currently, a crop of younger scholars are already raising these questions.

To end on a personal note, we’d like to ask you about a few of your favorite things…

a. Favorite way of managing notes and/or citations?

Old-fashioned notebooks or separate MS Word documents. I have tried Zotero and other applications but find the simple MS Word easier!

b. Best book in the history of childhood and youth you’ve read in the past year?

Catriona Ellis’ Imagining Childhood, Improving Children has been very helpful in thinking of similar questions in the 20th century. I also enjoyed reading the work of Sarah Duff on South Africa and Nazan Maksudyan on the Ottoman empire.

c. Favorite childhood book?

Tough to choose! I read quite a bit in my mother tongue – Malayalam – and English. The latter was influenced by global trends. I enjoyed Enid Blyton’s Noddy and Mister Meddle’s Muddle series, Gulliver’s Travels, but I also remember Maths with Mummy from Raduga publishers (Soviet Union) , and so many more.

d. Best piece of advice you remember receiving as a child?

Both my parents insisted that I be kind (although I am aware I wasn’t successful always) to everyone, including strangers. They were also very keen that I read, hear and learn about many things happening in the world, any subject, news, or even random trivia. They hated it if someone asked me what I thought about something and I just shrugged and said “I don’t know” or “It is boring”. One couldn’t get away after that!

Divya Kannan is Assistant Professor, Department of History and Archaeology, Shiv Nadar University Delhi NCR. She holds a PhD from the Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Her research interests include histories of Empire, education, childhood studies, labour, public history, and feminist studies. She is also the co-founder and co-convenor of the online Critical Childhoods and Youth Studies Collective (CCYSC).